- Research

Published: | By: Sebastian Hollstein

Many planetary systems consist not only of a central star and the planets orbiting it, but also of so-called debris disks. These regions contain small bodies such as asteroids, as well as large amounts of dust that is produced when rocky objects collide with one another. In our own Solar System, for example, beyond the orbit of Neptune lies the so-called Kuiper Belt, where larger debris is gradually ground down into dust.

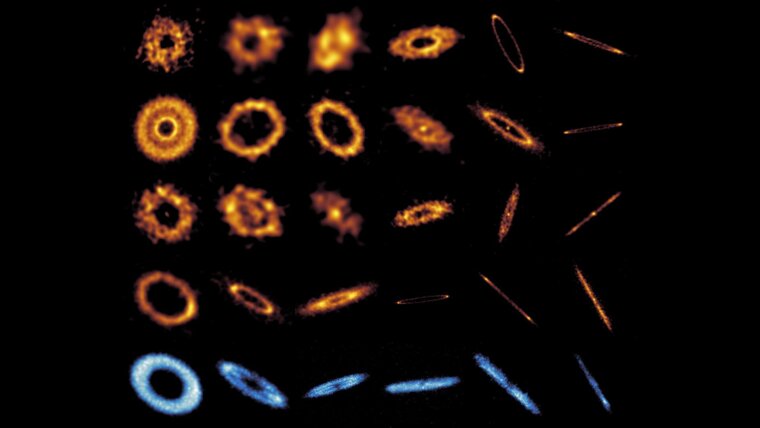

An international team of around 60 scientists—including astronomers from Friedrich Schiller University Jena—has now succeeded in imaging 24 of these debris disks in their planetary systems at high resolution. The project, entitled »ALMA survey to Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures (ARKS)«, used the ALMA radio observatory (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) in Chile’s Atacama Desert for the observations. The researchers report their results in several publications in the scientific journal »Astronomy & Astrophysics«.

Most of the imaged planetary systems are younger than 100 million years and are therefore in an early stage of their evolution, in which the formation of giant planets has just been completed, while Earth-like planets may still be forming. By comparison, the Solar System is about 4.5 billion years old. »Thanks to these new images, we are gaining for the first time such detailed insights into and new perspectives on distant planetary systems,« says Dr. Torsten Löhne of the University of Jena, who was involved in the project.

»We now have 24 different images with unprecedented resolution and quality, allowing us to learn much more about the structure of debris disks and their planetary systems,« adds his Jena colleague Prof. Dr. Alexander Krivov. »In addition, they tell us a lot about the formation processes of the respective systems and may even allow conclusions to be drawn about how our own Solar System evolved.«

Diversity of the Disks

The researchers are particularly fascinated by the unexpected diversity of appearances. Debris disks can consist not only of single rings, but can also form structures with multiple rings at very different distances from one another, broad halos—i.e. extended envelopes—or larger clumps within the rings. »The overall appearance and the fact that we can detect such disks in about one fifth of all planetary systems demonstrates a certain similarity among systems and their formation processes,« says Alexander Krivov. »However, the diversity of debris disks suggests that individual planetary systems undergo very different evolutionary paths. What causes this diversity is something we now need to find out.«

To this end, the Jena experts model, for example, the collision processes within a belt. Their aim is to understand how the dust visible in the images is connected to the invisible asteroids, and how the planets in turn influence the appearance of a debris disk, for instance by giving rise to a two-ring system.

For further insights, the astronomers measured the disks very precisely, determining, for example, their radial and vertical extent. This reveals how strongly dust and asteroids move within the disk and at what velocities they collide—the faster they move, the more extended the disks become and the more dust is produced. What influences these different velocities, however, remains to be clarified in future research.

Methods for Discovering Planets

In addition, data from debris disks provide valuable information about the planets in their vicinity—even though most of these planets are still unknown. »In only one third of the imaged systems do we already know at least one planet. In general, however, we suspect that planets are always present in the empty regions outlined by the orange dust in the images,« explains Torsten Löhne. »We can detect their signatures, for example, in the shape of the disk edges.«

»Current observational methods primarily favor the discovery of planets that are very close to their star. However, these planets can rarely explain the irregularities in the debris disks, as they are too far away from them,« says Alexander Krivov. »With the help of the newly obtained information, we may therefore be able to develop methods that allow us to find planets located more toward the outer regions of planetary systems—planets that have so far remained hidden from us.«

Gas in the Debris Disks

The Jena astronomers also expect further insights from a more detailed examination of individual systems. In some of them, they detected gas—predominantly carbon monoxide—which appears blue in the images and could reveal much about its environment. »We suspect that the gas is released during collisions between rocky bodies. If we can learn more about the composition of this gas, we may be able to infer what materials the neighboring planets and asteroids are made of,« says Alexander Krivov.

Further information on the project and the publications: https://arkslp.orgExternal link